Study: Cypress Point Club

A Marriage of Golf and the Natural Landscape

Fig. 1 17 Mile Drive ‘the Loop’ at Cypress Point Pebble Beach Resorts

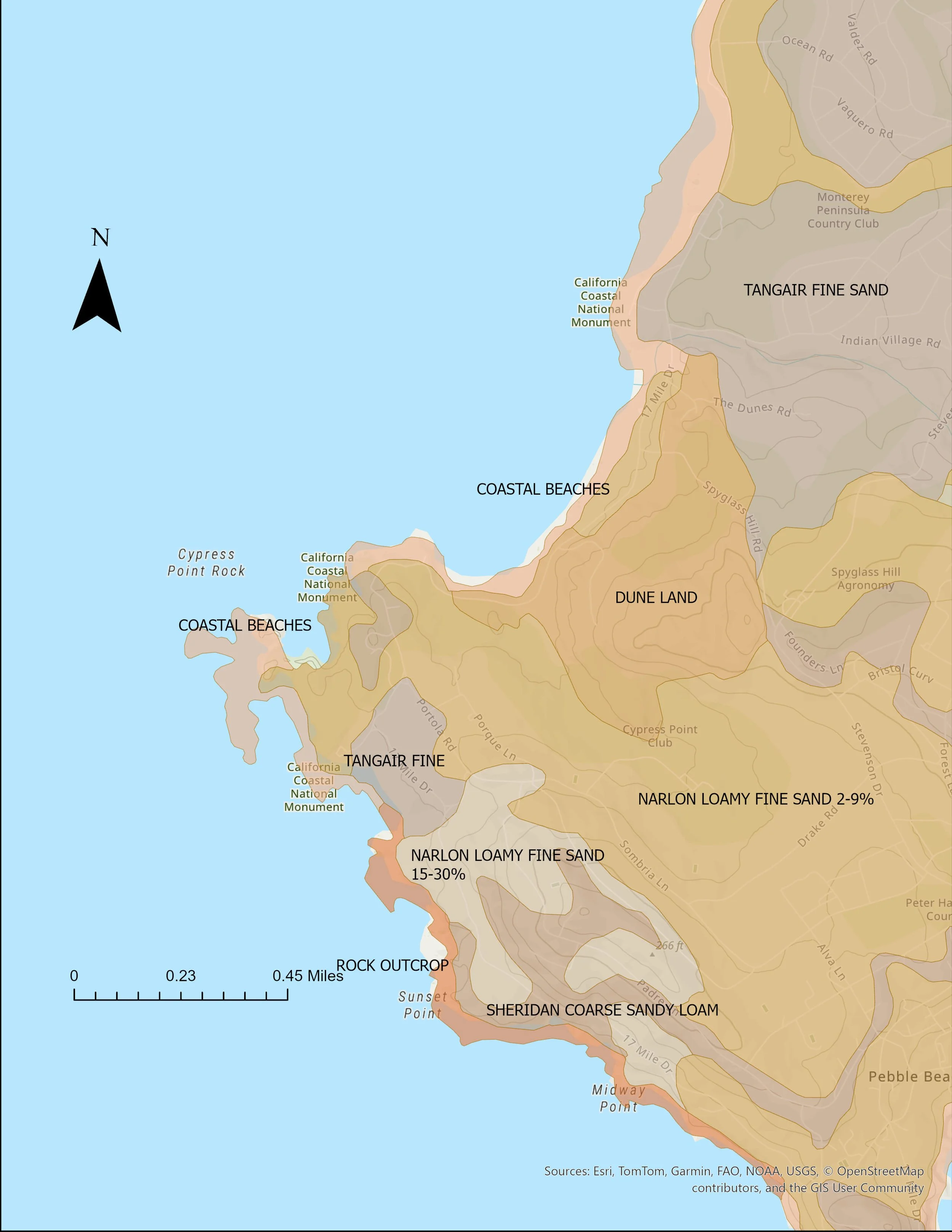

Fig. 3 Sand types at Cypress Point and surrounding areas GIS Community/Owen Mueller

Fig. 4 Robert Hunter Jr, Robert Hunter Sr, H.J. Whigham, and Alister MacKenzie before the 15th under construction

Geoff Shackelford/Julian P. Graham

Fig. 5 Aerial View of Cypress Point Google Earth 2022

Fig. 6 View of 17 Mile Drive and the coastline before construction of the 14th hole. Geoff Shackelford/Julian P. Graham

Fig. 7 The natural bunkering on the 13th hole

Michael Wolf

LA 212: History of Modern and Contemporary Landscape Architecture

Professor Christine Edstrom O’Hara

May 2025

The scenic coastline of the Monterey Peninsula became an epicenter of recreation for the American elite following the opening of the Del Monte Hotel by the Pacific Improvement Company in 1880. One of the many activities for visitors was touring the now-famous 17 Mile Drive by horse and carriage through forests, along craggy bluffs, and through rolling dunes. One of the trip's highlights would have been driving out onto the promontory that Spanish explorer Tomas de la Pena named La Punta de Cipreses in 1774. Translated to Cypress Point in English, the stunning piece of the California coast would receive attention again one hundred and fifty years after de la Pena’s visit.

The man responsible for this attention was Samuel F.B. Morse. Morse, a Yale grad, was appointed as manager of the Pacific Improvement Company (PIC) in 1916. His most famous contribution was bringing golf to the region. The PIC’s primary initiative was to sell homesites along the peninsula’s coastline, and in the area surrounding Carmel Beach and Arrowhead Point, the hillside properties were sold first. The initial plan was to sell more lots immediately along the coastline, but Morse proposed that the space be used to develop a golf course. This would preserve the views of the existing homes and the open space, as well as add another amenity to sell homes in the area. Pebble Beach Golf Links was built on the land, and today it is consistently ranked as the greatest public golf course in the United States.

Following the opening of Pebble Beach in 1919, Morse broke away from the PIC and formed his own development company, the Del Monte Properties Company. He purchased the 18,000-acre Del Monte Unit from the PIC, which included the Pacific Grove, Pebble Beach, the Los Laureles Rancho (Carmel Valley), and the Del Monte Forest. Morse continued the development of the area, and in 1922, he brought in East Coast socialite, sportswoman, and developer Marion Hollins. As the 1921 Women’s Amateur champion, she was given the position as athletic director of the Del Monte Properties, and

Fig. 2 Marion Hollins near the future site of the first green prior to construction. Julian P. Graham/ Loon Hill

helped sell real estate through her high society connections. She also had experience from founding The Women’s National Golf and Tennis Club on Long Island, which would open in 1923. As the development expanded, the question arose of what to do with Cypress Point and the surrounding area. Morse and Hollins determined that the area was too beautiful to be developed as homesites. In 1924, the idea of a golf club on the site began to take root. At the same time, the nearby Monterey Peninsula Country Club was also being developed by Del Monte Properties. Morse commissioned golf architect Seth Raynor to design the Dunes course at the Monterey Peninsula Country Club, as well as Cypress Point. However, Raynor died during the construction of the Dunes course, and after only having done a rough routing plan for Cypress Point in 1926. To replace him, Hollins recruited English golf architect Alister MacKenzie, whom she had met while competing in the United Kingdom.

Doctor Alister MacKenzie was born in England in 1870 to Scottish parents. He earned the title of doctor from his studies at Cambridge University, and his initial career was in medicine. He served the British Army as a surgeon in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), where he was inspired by the camouflage techniques of the Boers. The man-made landforms they constructed blended perfectly into the surrounding landscape, allowing the Boer soldiers to be completely hidden from the British. MacKenzie was inspired by this, not only for combat purposes, but for golf course architecture. In 1907, he would give up his medical practice to focus on golf course design. His first project was the design of the Alwoodley Club in Yorkshire, with oversight from architect Harry Colt. Design elements such as engaging strategy, variety, and naturalized aesthetics that would become hallmarks of his work were present in his first design. During WWI, MacKenzie briefly resumed his medical practice, as well as serving as a camouflage expert. MacKenzie’s career accelerated in the postwar 1920s, specifically after his commission to redesign Claremont Country Club, in Oakland, California, which brought him to the United States in 1926.

The quality of the site that MacKenzie was given at Cypress Point is arguably the greatest location for a golf course anywhere. Approximately one hundred and fifty acres of towering Monterey Pine forest, rolling white dunes, and picturesque coastline. In 1932, MacKenzie reflected on the quality of the site, describing it as follows; “I do not expect anyone will ever have the opportunity of constructing another course like Cypress Point as I do not suppose anywhere in the world is there such a glorious combination of rocky coast, dunes, pine woods and cypress trees.” But, with it being a site like no other there wasn’t suitable information on how a golf course could be developed in such an environment. MacKenzie’s associate, Robert Hunter, who supervised the project almost daily, would lead the process of gaining a better understanding of the site. Having taught as a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Hunter brought in former colleague professors to conduct studies of the site’s soils, vegetation, and drainage.

The soil makeup of the site is various types of natural sand including sheridan coarse sandy loam, tangair fine, and most predominantly narlon loamy fine. Sandy soils are ideal for golf courses, due to their natural drainage capability, which allows the turf to play firm and fast. As well as the malleability of the sand to construct features of the course.

Despite being mostly sand, the different areas of the landscape would still require different treatments to ensure turf health in the varying microclimates. To determine what seed, fertilizers, and topsoils worked best together, Hunter developed on-site test plots with different combinations of treatments on the existing soils. He ended up sending MacKenzie a ten-page analysis of the findings. This level of research was beyond standard for the time and led to the course being in exceptional condition quickly after completion.

Prior to the seeding, different areas of the property required different levels of preparation. The holes in the dunes required little work due to the malleability of the sand and the relatively little vegetation cover. But disruption caused by construction resulted in the need to stabilize the dunes to prevent erosion and blowing sand. This was done by planting shoregrasses in areas where the sand was left bare, as well as using small temporary fencing to hold the sand while the vegetation recovered. Holes along the cliffside required more work to clear some trees and add topsoil over the rockier base. An oversight on cliffside holes was the placement of features next to the cliff's edge. Which would eventually suffer erosion damage and require rock walls to be built to prevent further harm. The area that required the most initial work was the pine forest, where thirty acres of trees were removed to make room for wide fairway corridors. Dynamite was used to remove large stumps, along with road scrapers and four-man mule teams that were used to clear brush and grade the land. MacKenzie promoted these practices as well as the soil studies, saying the following: “We displaced much of the cost of the excessive cost of manual labor by the comparatively speaking low cost of mental-labor.” With these methods, the project cost came in below the 150,000 dollar budget at only 121,000 dollars (approximately 2,269,952 dollars in 2025), as well as being completed in an exceptionally quick time frame of less than a year.

In these landscape-altering processes, MacKenzie and his associates prioritized blending the artificial features that they created with the natural ones. Since the beginning of his career MacKenzie believed that the best looking features were ones that resembled or mimicked nature, having written in his 1920 book Golf Architecture; “The chief object of every golf architect or green-keeper worth his salt is to imitate the beauties of nature so closely as to make his work indistinguishable from nature itself.” Cypress Point is arguably his greatest implementation of those beliefs. This blending with nature was done on both the massive and intimate scales throughout the course.

The core behind how a golf course is designed is its routing; how it lies on and proceeds through the landscape. In his routing, MacKenzie had to work around the predetermined location of the clubhouse. Atop a hill and nestled into ancient Monterey Cypress groves, this location offers a vantage point to view the coastline and the surrounding course. Being close to the coastline placed it in the westernmost part of the property, forcing the majority of the usable land to one side. This led MacKenzie to not follow the convention of having returning sets of nine-hole loops, and instead having one loop of eighteen holes. While this may be seen as a negative, as players aren’t able to stop halfway, it allowed MacKenzie’s design to not be restricted and use the land to create the best golf holes. This leads to the course being one uninterrupted sequence, through the different environments in a way that makes the transitions even smoother. He also led players to acknowledge the landscape around them through foreshadowing. He did this by having the routing visit

highlights of the landscape, such as the coastline and dramatic dunes at various points. All of which built up to the coastline on the finishing stretch of the course on holes fifteen through seventeen. Instances of the coastline being highlighted prior include ocean views from the first hole and second tee before retreating into the inland parts of the property. The ocean is also previewed again from the high point of the eighth green and ninth tee, and finally arrives on the shoreline with the thirteenth hole. Not only does this make the course more visually appealing, but it also engages the players more by keeping the ocean in the back of their mind, despite not always being able to see it directly.

MacKenzie didn’t have absolute freedom in the routing due to the 17 Mile Drive that ran through the property. The road was moved inland from the prime coastal property, but still needed to reconnect to the coast on the property’s northern end. This needed to happen in the area where the fourteenth hole was to be located. MacKenzie wanted to maximize the coastline by having the fourteenth hole run directly along the shoreline near where the Fanshell Beach Overlook exists today. This would force the road to be placed between the fourteenth and first holes, and Morse worried about the safety of it being

in that location, “I am reasonably sure that it will result in the death of several people, for it will make a nasty mess in the middle of the golf links.” Morse’s concerns were heeded, and Hunter and Hollins supervised the alteration of the design, moving the road to the shoreline and pushing the fourteenth hole more inland. This design benefited the course, with the road only needing to be crossed twice and not deliberately cutting through the property. It also allowed for public coastal access south of Fanshell Beach.

On the more intimate scale, another feature of the course where natural blending was present was in the bunkering. MacKenzie implemented the visual deception he learned from the Boers while in South Africa to make the bunkers appear closer or farther than they are. This adds interest to playing the course by requiring players to play it multiple times to understand it. A quality of all great golf courses. Depth perception wasn’t the only illusion created, but also the illusion that the features are natural. More dirt was moved in the areas surrounding the bunkers and other features to tie the man-made features in with their surrounds, made easy by the sandy soil. Shaper Paddy Cole implemented MacKenzie’s staple characteristics, such as mimicking the outlines of trees in the outline, and jagged appearing natural edges. The naturalistic appearance of the features makes the course not feel imposed upon the landscape, but rather, a part of it.

Following the completion of the course, founder Robert Lapham remarked, “We gave the architects a free hand, and were more than pleased with the job when it was done… Dr. MacKenzie seems to have mastered the art of making everything look natural…” Cypress Point is an example of what can be created when an architect is given design freedom, an incredible site, and a group of knowledgeable people to collaborate with. It combines the natural landscape, strategic design to create picturesque landscapes. MacKenzie and his associates went beyond creating a golf course solely for the sake of playing a round of golf. They considered the landscape as one composition and sought to make the course a means of showcasing it. When hitting over the crashing waves of the Pacific, it is commonly acknowledged that it can be easy to lose focus on the sporting task at hand. What better testament could there be to an architect having created something that appears so beautifully natural than one being distracted by the environment that surrounds them?

Bibliography

“About | Pebble Beach Company History.” 2016. Pebble Beach Resorts. June 13, 2016. https://www.pebblebeach.com/about-us/company-history/.

Brawley, Edward Allan. 2008. “The Good Doctor, the Social Engineer, and the Golfing Gems of California.” California History 86 (1): 8–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/40495187.

“Club History - Cypress Point Club.” 2025. Cpcmack.org. 2025. https://www.cpcmack.org/club-history1.

“Cypress Point – the Alister MacKenzie Society.” 2024. Mackenziesociety.org. 2024. https://mackenziesociety.org/club/cypress-point/.

“Cypress Point Club.” n.d. Www.montereypeninsulagolf.com. http://www.montereypeninsulagolf.com/Cypress-Point-Club#google_vignette.

Institute, MacKenzie. 2020. “Alister MacKenzie Institute.” Alister MacKenzie Institute. March 6, 2020. https://alistermackenzie.org/articles/cypresspoint.

Johnson, Andy. 2016. “School of Architecture, Part 3; Tie-Ins” Thefriedegg.com. 2016. https://www.thefriedegg.com/articles/school-of-golf-architecture-part-3-tie-ins.

“Marion Hollins: Golf Pioneer.” 2025. Marionhollins.org. 2025. https://www.marionhollins.org/legacy.

Stanley, Adam. 2023. “‘The Whole Reason for Augusta National’: How Marion Hollins Became a Golf Course Design Pioneer.” Pga.com. PGA of America. April 4, 2023. https://www.pga.com/story/the-whole-reason-for-augusta-national-how-marion-hollins-became-a-golf-course-design-pioneer?srsltid=AfmBOorQgRf1a4bVggzhK44Ge08CqnZ5mcgc7e5VaXWfi8vrQskm15Ia.

“The History of 17-Mile Drive in 17 Photos.” 2019. Pebble Beach Resorts. May 3, 2019. https://www.pebblebeach.com/insidepebblebeach/the-history-of-17-mile-drive-in-17-photos/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2025. “CPI Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2025. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.